From the Heart and Chest

- 10 April 2013

EHI recently ran a profile of my friend Mike Fisher (who also happens to be a colleague as he is visiting consultant at Liverpool Heart and Chest, as well as being a chief clinical information officer and a consultant at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital).

The piece focused on Mike’s role as a CCIO. But his comments about Royal Liverpool’s decision to not scan historic paper records as part of a big electronic document management project piqued my interest, as this has been a live discussion at my trust.

For those of you who didn’t catch my first column, Liverpool Heart and Chest is due to go-live this summer with a comprehensive electronic patient record system from Allscripts.

Our project plan was written to “scan-on-demand” historic notes. But when we began scoping our exact approach, the true magnitude and complexity of the task at hand became apparent.

Also, I came to realise that the scope of the issue is not really confined to the notes that you are going to scan but instead to the entire “back-file”. Our own calculations are that over the next three years we will deliver care to 36,000 patients who have existing notes; but this represents less than a quarter of our notes estate.

One thing that I am determined about is that this estate will not grow. Clinical staff won’t touch the historic paper record after go-live, and those aspects of documentation that remain on paper will instead be scanned as soon as practical.

“Mostly harmless” (or mostly useless)

So what to do over the historic back-file? Could we get away with scanning nothing as they are typically, in Mike’s view, a “disorganised pile of crap.”

Our notes are quite well tabulated and organised in comparison to many, but even so I nearly agree about their overall value.

I was put in mind of Ford Prefect, the ‘Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’ roving reporter, who updates Earth’s entry in the eponymous tome from “Harmless” to “Mostly Harmless”. The historic paper record is mostly useless, but not completely.

Most of our outbound correspondence for more than ten years is saved as word files and can be read on the network, but that doesn’t give us the inbound correspondence. Prior records of in-patient care have little interest, but (for my clinical work) old operation and procedure notes are invaluable. And so on…

We ended up with an extensive exercise looking at ways to “de-composit” the notes in a manner that did not introduce risk and did not create a processing cost that exceeded the money saved from not scanning.

We have ended up with a good compromise, which involves taking out limited bits that would have been costly to scan, but minimising our risks by not trying to be too clever. As to what we do with residual records (both the bits that we take out, and also the notes that we never end up accessing), we are still deciding as an organisation. I have already made up my mind, however.

The notes need to be retained for a minimum of eight years since last care contact, but the period is longer for cancer patients, clinical research patients and others and those are poorly tagged.

The solution is obvious – we will store them in a big room, and scan them on demand if needed. After 21 years, I will personally walk in there with a can of petrol and douse the lot, and take great pleasure in tossing a lighted match over my shoulder as I walk out.

It’s all about the end user

The other big, live issue has been our build. My philosophy has always been to build a system that served the end user. If you build something that is intuitive, easy and clean then you will get good adoption and high quality data entry.

The system should not force people to make decisions that aren’t within their remit. If you force them to do so then all that happens is that people enter something to get off the page. Sadly not all share my philosophy – they want to reinvent human nature to fit their preconceptions rather than pragmatically accept the world as it is.

Such are the travails of being a clinical lead, but the question I wanted to put to all of you is ‘how does one decide what is the best approach?’ I am confident that my present adversaries adopt their position because they think they know best, but to me, it is obvious that I know best. Result – loggerheads.

In practice, however, this isn’t really my view. I realise is that I am not the expert on EPR; my supplier is. We are lucky to have an experienced programme manager called Jason over from the US who has activated multiple sites with an EPR.

Being as I am the customer, he doesn’t tell me what we should do – I have to ask him. His usual reply (in a heavy mid-western US accent) is: “Well, what we generally see is …” I have learned that this is code for “you don’t have to do it this way, but if you don’t then there is an excellent chance that you’ll regret it!”

After that, it is about the end user, by which I mean the clinical staff on the shop floor and not our senior clinical staff. The shop floor staff know how care is delivered in practice. The senior staff may direct the required end result, but often have no concept of the underlying process.

One particularly amusing example was a consultant informing the EPR team that we didn’t need to build an order for patients to be reviewed by physios and dieticians because this happens “automatically”. He was a bit surprised to have someone snap back at him “so how do they know they are in? Do the fairies tell them?”

So that’s where myself and the EPR team fit in. We might not be the experts in the EPR, or the experts in what is needed by the organisation. I like to think that we are the experts in translating between the two. Nice to know we have a role…

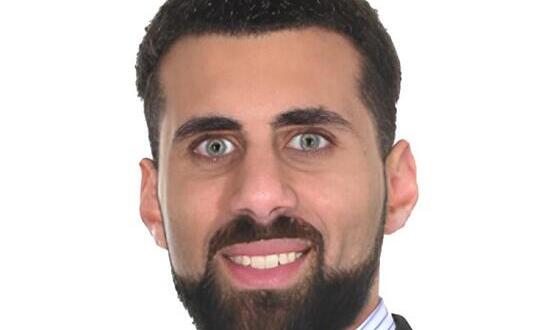

Dr Johan Waktare

Dr Johan Waktare is a consultant cardiac electrophysiologist at Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital, specialising in interventional procedures for heart rhythm disorders. He is the clinical lead on the trust’s electronic patient record project, as well as being a clinical lead for IT and the trust’s Caldicott Guardian.

A self-confessed IT geek, Dr Waktare has always been interested in computer hardware and software. His status was cemented when, several years ago, the IT helpdesk agreed to replace a user’s PC rather than look at it – after hearing that he had failed to repair it.