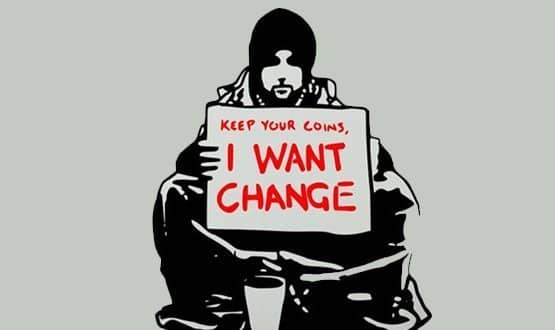

Power to the people on the high cost of change

- 10 June 2014

OK, so it’s a clichéd question, but tell me again: Exactly why is it that the NHS is so much worse at innovating than Apple, Google or Facebook?

Why wasn’t public health in the lead with its own version of Spotify for health information? Why wasn’t Fit Bit developed by cardiologists?

Why is that it every single chief executive that I meet in the digital health small and medium sized enterprise sector complains about the appallingly high cost of sales to the NHS: with many choosing to sell abroad rather than face the death by indecision that is the health service?

Standard answers include risk aversion, complexity of health, vested interests and a lack of competition – or was that integration?

But these just beg the question: Why is the NHS so much more risk averse than, say, the car industry? Or more prone to vested interests than publishing? Why is it that DVLA can build an excellent Road Tax renewal site, but NHS England can’t build a decent Choose and Book platform?

High transaction costs

Part of the answer is that change within the NHS generates abnormally high transaction costs. Transaction costs are the expenses associated with the institutional costs of doing business – the costs of operating in a market, the costs of conforming to information governance, of keeping multiple stakeholders happy.

Transaction costs lie beyond the direct costs of making the widget or performing the cholecystectomy, and beyond the indirect costs of managing the support staff, beds, parking, running a comms department and so on.

If you have ever sat in partnership meetings, on a governance committee, negotiated with the clinical commissioning group/trust or argued about budgets then you have contributed to that bundle of fun known as transaction costs. Yep, to know them is to love them.

The standard ways to reduce transaction costs in business include: reduce regulation, merge to get economies of scale, re-engineer business processes, reduce variation, tweak incentives, integrate databases, provide more management, or add more competition.

To which the NHS can pretty much say: “Been there. Done that.”

Driven by many stakeholders

When it comes to generating change itself (rather than delivering services directly) transaction costs are highly related to the number of stakeholders involved.

Compare Cross Rail (a highly complex multi-billion pound rail project being delivered more or less on time and to budget) to High Speed 2 (a highly complex multi-billion rail project already mired in delay). The first has relatively few stakeholders; the other involves everyone and his dog all the way from Euston in London to New Street in Birmingham.

The NHS is in a class of its own when it tries to innovate because it is (rightly) subject to multiple conflicting accountabilities. Accountability to the patient, the payer/commissioner, the tax payer, the local community, the professional community, the research community, pharma, the educational industry.

In short, Uncle Tom Cobley and all. More HS2 than Cross Rail. At this point, those fluent in NHS-speak will start to speak of consultation, involvement and partnership. And when you hear the NHS signing this particular tune you know you’re in high transaction cost country.

If this analysis is true, then the NHS’s inability to change is only going to get worse. If ‘joined up care’ means more stakeholders and more agendas, then joined up care, pooled budgets, partnership working and all those other nostrums are part of the problem – not part of the solution.

Meanwhile, out on the web…

So are there any answers to this conundrum? Well, look around in your non-working life and you will see the exact opposite to the NHS’s situation. For citizens, the cost of change – of doing many new things – is falling not rising.

It doesn’t matter whether you are talking about the costs of getting organised to oppose a local hospital closure, tracking the amount of exercise you and your friends do via a Fit Bit group, or Skyping the children in New Zealand. It’s all getting easier isn’t it? Stuff you couldn’t do five years ago is now humdrum.

Normally, we take this as just tech and the market working its wizardry. And at one level it is just that. But deeper drivers are also at work.

Network effects play a big part: the more people who use Google, the more accurate your searches will be; the more people who tweet the more useful you yourself are likely to find Twitter.

Network effects drive the increasing returns to scale behind social media and all other rapidly inflating digital phenomena. Instead of the decreasing returns to scale to which the dear old NHS (or any large hierarchical organisation) is subject, network effects mean that in our on-line lives you and I experience increasing returns to scale.

And out of this comes the another, less well known reason why the transaction costs of change are less for networks than they are for traditional bureaucracies.

As participation in a network reaches into the tens of thousands, that small proportion of people who wish to contribute and make something happen can allocate their resources and energies into the areas they are keenest to work on.

Instead of the traditional, costly ways of motivating people – managers, 1:1, targets, plans, meetings and, of course, paying people – networks at scale have the potential to find self-motivated, self-allocating, self-governing sub-networks that begin to collaborate independently to produce the things they want for free.

Witness Wikipedia and Linux. Or, in a different way, the Cochrane Collaboration and the Creative Commons licencing system.

Time for disruptive, NHS networks?

Truly networked formats have yet to fully emerge in healthcare and until they do talking about them has an air of unreality – just as the idea of Wikipedia seemed completely implausible before it actually emerged.

But look at the big picture: slow moving health service bureaucracies (both public and private) process millions of patients each day, but are mired in high transaction costs that mean the cost of innovation keeps rising.

Outside these citadels seethes the network with its access to the infinite monkey puzzle of information, high levels of motivation, low costs of collaboration and nothing to lose.

Like the proterozoic sea from which life emerged, so the building blocks of the new ways of delivering healthcare can already be seen out there on the net. (Take a look at IBM’s Dr Watson, Cell Slider, or Scandu if you want to see a quick subset of these organelles for the new order)

The one thing the citadel does, of course, is to keep its mitts on the money. But the US is abuzz with suggestions for crowd funding disruptive healthcare innovations. No match for the £120 billion the NHS gets through each year, but a start. And perhaps the first whisper of the perfect storm to come.

Paul Hodgkin

Paul Hodgkin is founder and chair of Patient Opinion, a website on which patients, service users, carers and staff can share their stories of care across the UK. Patient Opinion is a not-for-profit social enterprise based in Sheffield.

Until 2011, Paul also worked as a GP and has published widely including in the BMJ, British Journal of General Practice and the Guardian and the Independent. Follow him on Twitter @paulhodgkin.