NHS-backed apps put patient data at risk

Dozens of apps that feature in the NHS Health Apps Library put the privacy of patient data at risk, according to a paper published in the open access journal BMC Medicine.

Research carried out by Imperial College London and France’s Ecole Polytechnique CNRS showed that out of 35 apps in the library that sent identifying information over the internet, 23 did so without encryption.

Four apps were found to be sending both identifying and health information without encryption during the review, which assessed 79 apps in the library during July 2013.

Just 53 apps had a privacy policy and for 38 apps transmitting information over the internet the privacy policy did not state what personal information would be sent.

Lead researcher Kit Huckvale, of Imperial College, London, said: “Our study suggests that the privacy of users of accredited apps may have been unnecessarily put at risk, and challenges claims of trustworthiness offered by the current national accreditation scheme being run through the NHS.

“The results of the study provide an opportunity for action to address these concerns, and minimise the risk of a future privacy breach.”

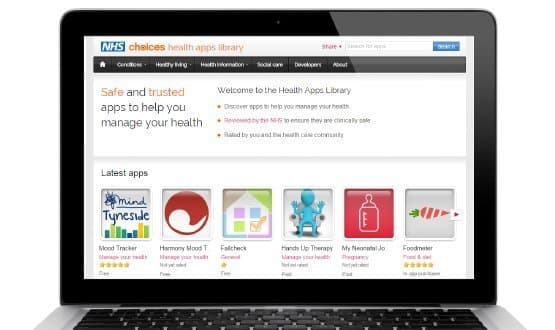

The NHS Health Apps Library was launched in March 2013 as part of NHS Choices. It is meant to serve as a resource of “safe and trusted” smartphone and tablet apps that have been reviewed by the NHS.

This is not the first time the library has come under fire, however, with health data privacy campaign group medConfidential criticising its review criteria over the summer.

These concerns led to the removal of mental health app Kvetch and Spanish-owned Doctoralia being removed from the service in July.

In blog post in August, medConfidential’s Phil Booth said: “To be included in the NHS Apps Library, there must be far tighter restrictions on data transfer, sale and exploitation.”

The report in BMC Medicine adds weight to these comments and comes at an important time for NHS England, which is looking to develop a new endorsement model for healthcare apps as part of the ‘Personalised Health and Care 2020’ framework.

A specific mental health ‘app library’ was launched as part of this process earlier this year and there are further plans for similar resources for diabetes, smoking cessation, maternity and end of life care.

Paul Wicks, vice president of innovation at health information sharing website PatientsLikeMe, recommends five approaches to improve the quality of medical apps in an accompanying column in BMC Medicine.

These include educating consumers and the creation of an app safety consortium of developers, researchers, regulators and patients to identify harm that can arise from health apps. He adds that there should be enforced transparent of apps and an active review of every medical app to be led by the app stores.

Most significantly, he recommends a review of every medical app to be conducted by a health regulator, such as the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

He says: “The potential for benefit remains vast and the degree of innovation is inspiring – but it turns out we are much earlier in the maturation phase of medical apps than many of us would have liked to believe.

“To build the future we want, in which patients can trust their medical apps, we need to verify that they function as intended.”

Responding to a request from Digital Health News, a spokesperson for NHS Choices said: “It’s important that all of the apps listed on the NHS Health Apps Library meet the criteria of being clinically safe, relevant to people living in England and compliant with the Data protection act.

"We were made aware of some issues with some of the featured apps and took action to either remove them or contact the developers to insist they were updated. A new, more thorough NHS endorsement model for apps has begun piloting this month.”

They added: "The apps that appear on the NHS Health Apps Library have been reviewed and found to be clinically safe, relevant to people living in England and compliant with the data protection act, they are not formally ‘accredited’ or ‘endorsed’.

"All feedback on apps that appear on the site is looked into and if the apps in question are found not to meet these three criteria they are removed."

Existing efforts to create guidelines for the use of medical apps include a set of standards for developers published by the British Standards Institution in May this year.

The Royal College of Physicians also published guidance this year recommending its members only use medical apps with an official CE mark.

However, this was heavily criticised by Charles Lowe, managing director of the Digital Health and Care Alliance, who said it would discourage doctors from using apps that can improve efficiency and patient outcomes.