Joe’s view: Can the NHS bear to be special?

- 26 January 2016

Jack Kerouac called it the “dark days of a guy’s early twenties”. I don’t know if Kerouac studied psychology at all, but the godfather of developmental psychology , Erik Erikson, also believed in the dark days of a guy’s early twenties.

In fact, Erikson had an entire theory of personality development which outlined eight stages of development from cradle to grave and bore more than a passing resemblance to Shakespeare’s seven ages of man, as described in ‘As You Like It’.

Erikson described each of his ages as a “psychosocial crisis” and the one pertaining to a guy’s early twenties he called the “intimacy versus isolation” crisis.

Or to put it another way, the twenty-something person battles with “I just wanna keep on having fun” and “wouldn’t it be nice to fall in love and settle down with someone special?”

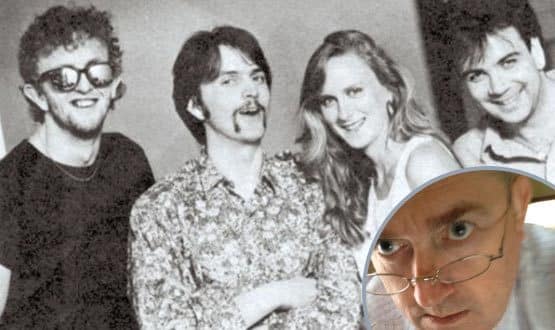

This dilemma is achingly summed up by a song I came across in 1984, when the North East melodic angst combo, Prefab Sprout (pictured), released their brilliant debut album ‘Swoon’.

The song, ‘Couldn’t bear to be special’, opens with the lead singer, Paddy McAloon, audibly wrestling with his intimacy versus isolation psychosocial crisis and the album formed the background music to my own.

Happily, by 1990 my crisis was resolved. I was married, we were living in our first home, we had a baby on the way. I was practically a grown up.

Not long after we moved into that first home, we got a new neighbour. Imagine my amazement – and instant return to adolescence – when the new neighbour was none other than Martin McAloon, bassist of Prefab Sprout and brother of Paddy, who had penned ‘Couldn’t bear to be special’.

Meeting Martin for the first time, I blurted out what a big fan I was. But Martin was resolutely decent and non-pop-starry. Our wives had babies within months of each other and we all got along famously (well, in a normal-good-neighbours-not –famous-at-all way).

My daughter, Emily, and Martin’s son, Johnny, remain in contact with each other even now; despite being in the dark days of their early twenties.

Siri, write me a record

‘Couldn’t bear to be special’ continues to pop into my mind on a regular basis despite the passage of time. That’s not because I am in the psychosocial crisis of my age (stagnation v generativity, age 35-64), but because I can no longer bear to be “special”.

In particular I am tired of being “NHS special” and paying the special price that goes with it. For example, I have noticed that – after a slightly shaky start – Siri on my iPhone is increasingly capable.

It rarely puts a foot wrong when I ask it to look something up on the internet for me. In fact, I can use it to dictate letters and emails if I am in a quiet environment and it types more accurately and spells better than some typists I have had.

So why not use it to dictate NHS letters? Why not use Apple’s expensively developed speech recognition technology to dictate direct into my electronic patient record?

Because I am “NHS special” and I must be sure that the data is not, however briefly, going to Cupertino and infringing information governance rules.

Instead, I must buy an “NHS special” speech recognition package at a cost that is infinitely more expensive than Siri (free with the device and no annual licence fee).

Indeed, I must buy ones that are ten times more expensive than similar – but non “NHS special” – consumer speech recognition packages (available for a small, one-off fee) that can do the job perfectly well.

The banks didn’t do this

Going back to the 1980s, I was an early adopter of telephone banking and later internet banking.

I am sure that the banks must, for a time, have considered whether they would need “banking special” telephone networks that would involve them in laying their own network of copper across the world that would be accessible to only the bank.

Perhaps one bank spoke to other banks about sharing the costs of developing “banking special” telephony and internet facilities.

In the end, however, they decided to go with the public telephony and the internet. Perhaps because they recognised the pace of change would leave “banking special” telephony and internet lagging years behind.

Perhaps they realised that at some time or another they would need to interface with the general public who, by definition, could not have “banking special” communications systems.

For one reason and another, the banks realised that they could ride the wave of rapidly developing consumer communications and add the necessary security and authentication apparatus as required. They did not need to develop a separate system.

The NHS did not come to the same realisation. There are 60 million NHSmail 3 accounts. Yet it’s quite unclear whether N3, the “NHS special” internet, will be able to cope with the growing demand for bandwidth that on-line video consultation and on-line correspondence with patients is likely to throw up.

Time to learn from the opposition

The NHS’ online rivals, like Babylon, are managing to leverage consumer communications systems, apps and the cloud to deliver services.

These rivals deliver security that paying patients are happy with. And they are doing it at a price that the NHS may struggle to compete with.

Meanwhile, there are great consumer apps, superfast broadband and 4G Networks out there developing at an amazing pace, driven by massive market forces we can only dream of in healthcare.

Siri, Office365, Cortana, Google, Whatsapp and similar are all waiting to be stitched into the healthcare market place; if somebody can get the security wrapper right.

The Netflix approach – building your business on somebody else’s expensively developed infrastructure – is being widely adopted by the private health market and may be something the NHS needs to adopt to survive.

It’s not a case of ‘Couldn’t bear to be special’ for the NHS; more a case of the NHS “can no longer afford to be special”.