Joe’s view: of consent models

- 10 October 2016

I am 48 days away from retirement, and I think I’m about ready to go. When he died at the age of 67, my father was the longest lived of nine siblings.

“The McDonald men are built for speed rather than endurance, son, enjoy every day – it might be your last,” he told me. Consequently, when I heard that psychiatrists get to retire at 55 this played a part in my choice of career.

Unsurprisingly, at this late stage of that career, I have begun to reflect on my 30 years as a psychiatrist and whether I have the emotional stamina to carry on.

I have decided that I’m too old to carry on in clinical practice in a health service that is increasingly in need of young men. I probably won’t miss not really enjoying 'Match of the Day' on a Saturday night because I’m wondering if I’ll get called out.

I probably won’t miss the 3am phone call on a Sunday morning asking me to go and see a 17-year-old in a police station in Gateshead. I definitely won’t miss dressing silently in the dark to avoid waking my wife, then tripping over the dog, half asleep.

Or scraping the ice off the car windscreen and then driving slowly through the snow, wishing I’d bought a four-wheel-drive vehicle. Or standing at the desk waiting for the custody sergeant to fill me in on the details of how the young person came to be in custody.

Pulling people out of a nightmare

In the car, for just these kinds of journeys, I have an on-call playlist to cheer me up. On top of that list is the song ‘Better Day’ by Ocean Colour Scene, which contains the line “and then the nightmares come and you get blown away.”

The first time you have an episode of psychosis, you literally wake up in a nightmare. Your friends and family may have been replaced by droids who look exactly like your family.

The illuminati may be plotting your death and – worst of all – you can no longer trust any of your perceptions so that you will see things and hear things that other people cannot see or hear but that will be real to you.

The thing I will miss is that when I recognise that somebody is having their first episode of psychosis, I can reach into their nightmare and pull them out.

The first part of this process is convincing the patient that you understand the nature of the nightmare. To do this you have to join the patient in their world and take a share in the nightmare.

When the patient realises that you are there to help and genuinely on their side, you can begin to walk them out of the nightmare. That connection, that feeling, is the best feeling in the world. I will miss that.

I want to see an end to psychosis

The treatment of psychosis has improved hugely during my 30 years in the game and the prognosis of people with psychosis is far better than it was.

However, I had hoped that, in my time, we would see an end to it. No more terrified teenagers in police cells or emergency rooms, no more reaching into the nightmare. It was with this hope that I got involved in health IT.

If we could flow enough data from enough cases of psychosis and link phenotypes to genotypes, then maybe I could get rid of psychosis and prevent the nightmare.

It was therefore frustrating that we didn’t achieve more during the National Programme for IT to join up electronic patient record systems across the NHS to produce the consent-rich research environment that we need to get rid of psychosis – or cancer, for that matter.

We ran aground again and again on information governance, consent models and infinite debates about privacy and confidentiality.

Escaping the information governance nightmare

Information governance and getting consent to link datasets from research is an incredibly complex subject and cleverer people than me, not least Dame Fiona Caldicott, have attempted to make sense of it all.

I recently spoke to David Whitlinger, who heads up the New York eHealth Collaborative, and he told me that to get consent for research from millions of people has taken large amounts of money, five years and a change in the law.

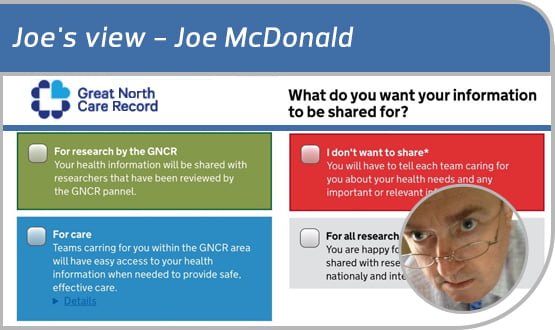

I was speaking to him as we plan to attempt to create a consent-rich research environment in the North East and North Cumbria for the Great North Care Record project.

Dame Fiona Caldicott’s most recent report spells out a very simple model. This retains the requirement to get informed consent from individual patients to use their data in research, but it also allows a large amount of data to be flowed for NHS purposes.

Outside NHS Digital and NHS England I detect very little enthusiasm for this model, which looks likely to do another lap of the continuous struggle between privacy lobbyists and sharing enthusiasts.

Simplicity and complexity

In an attempt to find another way – one that could reconcile the need for simplicity when citizens record their preferences around sharing with the need to use information for both research and NHS activities – I attended an NHS hack day at the weekend.

At the event in Newcastle, somebody helpfully pointed me to a presentation by Tom Loosemore, where he explains that the magic of IT is to allow the surface to appear simple but to accommodate complexity underneath.

With this revelation shared with a brilliant young team of hackers and old lags from the NHS like me, we quickly came up with prototype front end web app which would allow citizens to set their privacy settings on the healthcare data.

The next revelation was provided by looking at Microsoft HealthVault and Apple HealthKit, which have come quite a long way since I first looked at them a year or so ago.

Both HealthVault and HealthKit have developed infinitely configurable privacy settings in their health facing apps, so that those who wish to share all their health data can do so and those who are passionate about privacy in some aspects of their health can lock down individual data items.

It seems to me that a clumsy land grab, backed by legislation, for the patient’s data is shortsighted and ill-fated when the technology is already there to deliver ‘simple’ for the many and ‘complex’ for the few who are passionate about privacy.

Can we have a simple consent model interface for the citizen? Can we satisfy those who are passionate about privacy? I believe we can have it both ways. We intend to prove it in the Great North Care Record.

Knickers to retirement!

About the author: Joe McDonald is a practising NHS consultant psychiatrist and CCIO at Northumbria, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust. He is also chair of the CCIO Network. Follow him on twitter @CompareSoftware