Using AI assessment to tackle dementia in ultra-early stages

- 9 September 2019

As the NHS faces one of the biggest health crises of its generation, could artificial intelligence be key to fundamentally changing how – and when – dementia is diagnosed? Owen Hughes reports.

Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease continue to increase and remain the leading cause of death in England and Wales, accounting for 12.8% of all deaths registered in 2018.

The financial toll on healthcare services is huge: figures from NHS England and Dementia UK put the economic cost associated with dementia at £23 billion a year, a figure that is predicted to triple by 2040.

While there is no cure available, catching diseases like Alzheimer’s early on can help those living with the condition to slow its progression.

Cognetivity Neurosciences, a Cambridge University spin-out based in London, has developed an artificial-intelligence (AI) powered test designed to detect cognitive decline in its ultra-early stages – potentially detecting dementia and related conditions up to 15 years before a formal diagnosis.

The five-minute iPad test, which is currently undergoing clinical validation trials at eight NHS trusts, is designed to be administered as part of a patient’s annual health check-up, much as a GP would perform a blood pressure test.

Dr Sina Habibi, CEO of Cognetivity Neurosciences, argues that the lack of routine standardised screening for cognitive impairment is the reason dementia is often diagnosed far too late.

It’s also the reason nearly a third of people with Alzheimer’s in the UK die without ever receiving a proper diagnosis.

“The approach to diagnosing the disease has not changed much since 1901, when Dr [Alois] Alzheimers identified and characterised the first patients,” explains Habibi.

“The gold standard is still standardised tests, which are heavily memory-based. It’s like an exam you sit at the end of school: it gives you a score based on which you either pass or fail.”

Habibi argues that such tests are inherently biased as they require a degree of educational ability and can be ‘learnt’ over time, making the results unreliable.

This results in patients being wrongly sent to memory clinics for further tests, at huge expense to the NHS.

“At the moment half of referrals are wrong, and this is at the cost of thousands of pounds for memory clinics to the NHS,” he says.

“This is because there is no standalone diagnostic tool for Alzheimer’s. What is there instead is ‘differential diagnosis’ – you start the process by failing one of these tests.

“The memory tests are crude in themselves.”

Allowing earlier health interventions

Cognetivity’s triaging system is designed to detect cognitive impairment as part of a routine clinical assessment by a GP, and help them decide whether or not a patient should be referred to a memory clinic.

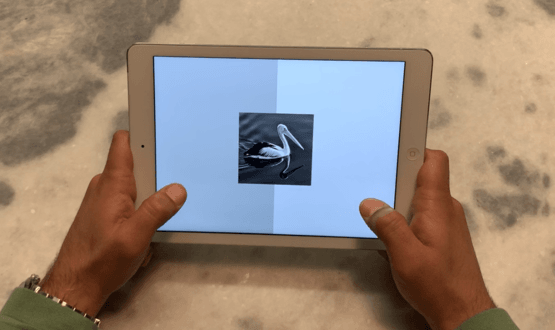

For the test, a series of images are shown to the patient, each one appearing on screen for a matter of milliseconds and ‘hidden’ within a sequence of TV static-like patterns.

The patient must determine whether or not an animal appeared in each picture by tapping to the right or the left of the screen.

The theory – according to Cognetivity – is that the human brain is conditioned to react more quickly to images of animals – an inherent trait believed to date back when humans were not at the top of the food chain.

Company co-founder Dr Seyed-Mahdi Khaligh-Razavi discovered this phenomenon while studying his PHD at Cambridge University’s Cognition and Brain Unit (CBU), Habibi explains.

“He was studying human vision and putting people through functional MRI (FMRI) and giving them visual tasks, to see what part of the brain is activated based on what stimulus,” he says.

“While doing that, he realised that there is a specific reaction or sensitivity of the brain to pictures of animals.

“We’ve now found that there are lots of theories around the ‘food or fear’ phenomenon: you either have to run away or run toward it.”

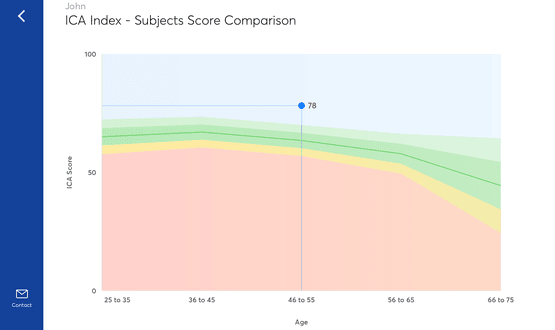

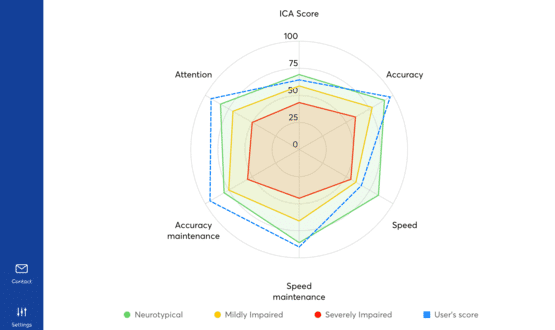

The test, which is underpinned by a proprietary machine learning system, scores each patient’s speed, accuracy and attention using a traffic light system, which can then be used by a healthcare professional to aid diagnosis.

Scoring in the red zone would indicate cognitive issues where a referral to a memory clinical would be recommended.

An amber score would indicate potential cognitive impairment, in which case the clinician may ask the patient to return to repeat the test at a later date. A lack of sleep, stress or certain medications could cause a dip in performance, Habibi explains.

Scoring in the green zone would indicate that a patient is performing in a healthy range. In such a situation, a GP may decide to take no further action.

Preventing the ‘masking’ of Alzheimer’s

Key to the test is that it activates a lot of the brain in a short amount of the time, Habibi explains.

Each image contains different mathematical characteristics, with animals easier to spot in some images than in others.

This means the brain must work harder to discern what’s in the image while still reacting at speed. Working in the brain in this way prevents it from ‘masking’ – a phenomenon observed in dementia patients whereby brain cells begin working harder to compensate for those dying off, concealing the disease’s effects.

This can mask the problem for several years, and is why dementia patients wake up one morning and suddenly can’t remember their children’s names.

“By making the test very challenging, we reduce the chance of masking,” Habibi adds.

The test also takes memory and learning out of the equation entirely.

“An animal is an animal in every culture – it’s just your speed of analysing the information,” says Habibi.

“When memory comes into play, learning is a factor. By isolating memory from this, we’ve taken the learning bias out.”

Cutting the cost to secondary healthcare

Cognetivity hopes to have acquired regulatory approval in Europe and the United States within the next year.

While the ultimate vision is to insert the test within GP practices, Cognetivity first means to target secondary care, where the cost of dementia is hitting hard.

“To build your argument you need to show cost-saving, not additional cost,” says Habibi.

“Where we want to start is secondary care, to help them filter out people who should not be going through the referral process.

“Memory clinics are the ones that are overrun and out of resources. The idea is that we can help them streamline and bring them the people who need to be seen, and filter out people who are wrongly referred.

“We need to showcase how the technology can save costs within the NHS. Then we can try to scale it up across the country.”

A new era for brain health?

The cognitive test is only one element of the larger artificial intelligence engine being built by Cognetivity Neurosciences.

In addition to its clinical application, the company has developed a consumer-facing app with Dacadoo that combines both physical and mental health tracking, the idea being that users can see how their physical health affects mental performance and vice-versa.

Cognetivity eventually hopes its medical app will be capable of pulling in data from other clinical systems to provide deeper insights on dementia and its causes.

“We can draw lots of different information about you – such as demographics, your health records, your pharmacology records – that can give us a better understanding of what impact all of this will have on your brain health,” says Habibi.

“Every day we find different applications and people come to us with different questions about how they can use it.

“Brain health is a very new concept. There’s now a whole science around it and it’s going to have a huge impact.”