Henrique Martins: ‘The UK needs to go big with harmonised large datasets’

- 17 December 2024

During his tenure as head of the Portuguese Digital Health Agency between 2013 and 2020, Henrique Martins was responsible for advancing the nation’s eHealth strategy, including projects such as the health information sharing platform for electronic health records (EHRs), the national electronic prescription service and vaccination records.

This experience led him to chairing the sub-group of the European Commission’s e-Health Network responsible for the establishment of the European eHealth Digital Services Infrastructure for cross-border health data sharing between 2018 and 2020. As a result of that starting effort, there are currently 14 countries exchanging health data across the European Union under the brand MyHealth@EU.

Martins is now a part-time professor teaching and researching digital health and leadership education and continues to consult on international digital healthcare projects.

Ahead of speaking at Rewired 2025, Martins shares his views with Digital Health News on why the UK need to “go big” with the forthcoming NHS 10 year health plan.

What do you enjoy about working on cross-border data sharing projects?

I’ve been given the opportunity to work with different countries, connecting healthcare systems through interoperable digital health services. In order to connect two countries and see health data flowing from one country to another, you have to align trust into an area where, normally, countries are very protective.

The UK is very proud of its NHS and the Belgians are very proud of their completely different health system with insurance companies, private hospitals and public hospitals. You need to align these different actors, make them trust each other, and align their software, which is often very different.

You also have to work at the technical level and understand how to go down the route of the standardisation and harmonisation of datasets.

Finally, you have to convince clinicians and patients that data from one country can be usable in another country. That’s a foreign concept, because people don’t associate healthcare as something that you can consume cross-border.

In Europe, there are around 25 languages and very different cultures, but the data has to move from one system to another in a clear, programmable way. From all this complexity, it has to work at an operational level. It’s thrilling because it’s a social technical effort and I enjoy that.

How do you persuade clinicians to see the benefits of sharing data cross-border?

Portugal was one of the first countries to pilot the epSOS project for cross-border sharing and we chose allergies as an entry point.

Back in 2013, we used allergies because clinicians are sensitive to the idea of patient safety. If you tell them that this data might contain relevant allergy or medication data needed to avoid harming a patient, this talks to their Hippocratic oath.

Today, we also use vaccines as an entry point because of COVID. People are aware of the idea that knowledge of their vaccine status can literally open borders or close them.

Doctors are sensitive to the idea of a system giving them information that allows safer care. When it is concrete things like allergies or vaccinations, this is simple to grasp, rather than trying to solve all the problems of healthcare.

How can we reassure citizens that it’s safe for their data to be to be shared cross-border?

We know that the level of sensitivity is different in different countries. For example, in Germany, there’s a lot of concern about data sharing for historical reasons.

In many countries, cross-border sharing is voluntary, so you have to opt-in to it. We were lucky in Portugal, that we did an opt-out and only 0.01% of people have chosen not to share their health data within the country. If you want to opt-out you have to proactively go online and say ‘I do not want my hospital data shared with the GPs’, for example.

But for any data going out of the country, you have to proactively go to the website and opt-in. You can give permission for a few hours when visiting a country and turn it off when you get back.

Taking paper records abroad also has risks. Paper can get lost, stolen or destroyed

The process has to be simple and seamless to gain citizens’ engagement. I remember when I was living in the UK, there was a paper sent to people’s houses for them to write a letter to the NHS to opt-in or out. I’m not criticising, but this is not the way. It has to be flexible and easy.

People should be educated in the risks and in cyber security aspects, but they need to know that taking paper records abroad with them also has risks. Paper can get lost, stolen or destroyed, which is also an issue.

What advice would you give to the UK government and NHS on creating a unified patient record?

I had the opportunity last week of having an online call with colleagues from the NHS Digital who are building this and I’ve conveyed some advice.

I was happy that they were interested in what’s happening outside the UK because it shows that they are open to cross-learning. There are things the UK is doing that other countries can benefit from learning about and vice versa.

Sometimes it’s easier to secure one big fort than five medium-sized forts

Portugal is a 10 million population country with an NHS like England. The only difference is the population number, but I don’t think that makes a difference anymore. A few years ago it would have done, but today there is cloud computing and large databases, so whatever you design for 10 million people can also work for 50 million.

My first suggestion is to go big and be courageous enough to have harmonised large datasets, even if people are afraid about cyber security risks. This will position you closer to other types of capacity in terms of analytics, AI modelling, and even the security of data. Sometimes it’s easier to secure one big fort than five medium-sized forts.

The other thing we have learned, in countries that have advanced with patient portals and interaction with patients and apps, is that we tend to the data that we have, rather than asking citizens what data they want.

We did exercises with groups of people in Portugal and found that people want very simple things like to know in real-time what pharmacies and hospitals, emergency rooms are open and whether they have parking.

We often think people want to access all their health data, and some people do, but many just want not to be asked the same question twice. If they said in one hospital that they are allergic to strawberries, they expect allergies to strawberries to be known everywhere.

This is what makes a national EHR. Anything else is not national, it’s segregated.

How much of a big job will it be for the UK to make a national EHR?

It is a big job, but you start by splitting the data categories. This is what we are doing at the EU level, and we did the same at the country level. Spain finished this many years ago.

You don’t have to have everything available at the same time on the national level. Of course you want the entire record there eventually, but, you have to go stepwise. This is what makes or breaks a national project.

I don’t trust projects that promise all records to all people online on day one. It’s not realistic

With allergies for example, it means that for every software, the nurse or doctor that introduce an allergy, introduce it in the same way. You have to train them and create a code and change the software. Then the allergies are stored at national level or sub-regional level, whatever architecture you want. This is a small, simple set of data, but it provides immediate value, because all prescriptions can be verified against all allergies to all UK citizens.

I don’t trust projects that promise all records to all people online on day one. It’s not realistic. It’s better to say next year, we’ll have 80% of this type of data, the next year, that type of data moves to 90% and so on.

It is a big task – especially in the UK, where NHS trusts are very heterogeneous. There are hospitals that have advanced software and others that are still struggling with a lot of paper hanging around the wards.

That’s a lot of work, but the UK has done big things in many other areas.

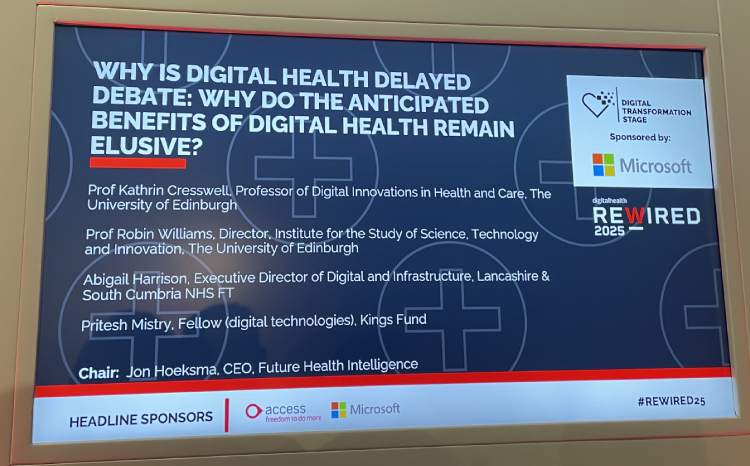

Can you give us a taste of what you’ll be talking about at Rewired 2025?

The idea is to share different perspectives on what’s happening outside the UK that could be inspirational. I’ll be bringing a bit of what’s happening with the European health data space regulation which was approved this year.

There are different initiatives around the world exploring the international patient summary, which is a global standard to which the UK agreed to a few years ago as a G7 country.

The idea I want to share is not to just connect the UK. Connect the UK to the world and through that process, you’re more likely to quickly connect the UK.

Martins will be speaking at Rewired 2025 at the NEC in Birmingham, 18-19 March 2025. Register here.

The event is co-headline sponsored by The Access Group and Microsoft. Alcidion, Nervecentre, Solventum and Cynerio are also sponsors.